After reading Michael Sugich’s excellent book, Signs on the Horizons, I felt a desire to travel back to Morocco and try to gain a taste of the things Sidi Michael had experienced during his early years in Islam. I travelled to Morocco five years ago, back then I was more of a tourist, and I didn’t know as much about the history of Sufism in Morocco at the time. The Morocco I had visited was a world away from what Michael describes in his book, and even he admits by the 80s spirituality was slowly dying away in the country, being replaced with the materialism and desire for worldly gain that many visitors to Morocco now experience. Regardless, I decided to make an intention and go off the beaten tourist track and to visit the many awliya buried throughout the country.

My first stop was Marrakech, ironically this was where my last trip had finished, and it felt like I had come back to carry on where I had left off. The main part of my visit to Marrakech was to visit the ‘seven patron saints’ of the city, particularly Shaykh Sulaiman al-Jazuli, the writer of Dala’il al-Khayrat and Qadi Iyad, writer of al-Shifa, both of these being books I had become acquainted with since my last trip to the country. There isn’t much online about how to find the locations of the saints’ tombs, but they are marked on Google Maps. For the benefit of anyone who wishes to visit them, I’ve marked them out here with walking directions (Edit: Those walking directions don’t tend to work so well, and it seems there isn’t actually a listing for all the shrines anymore, so I’ve created a Google Maps List of the seven saints instead). A lot of people don’t realise that Google Maps comes with an offline facility, you can download specific areas to your phone with your favourites included. I cannot stress the benefits of using this feature enough, especially in a country like Morocco where you will be lost more than half of the time. I had a young faux guide show me to the first four, though I didn’t really want him to, and I paid him way more than I should have. If you mark the locations down you should be able to make your own way round. The only one I had difficulty finding myself was Sidi Es Soheili, his zawiyah is located next to the king’s palace, so if you make your way around it eventually you will find it. The only one I wasn’t able to visit was Sidi Yusuf bin Ali, as it was closed, but all the others should be open for most of the day. The following day I went back into tourist mode for a while and booked a day trip to the Atlas Mountains. Though one thing I learnt from my trip to Kota Kinabalu, is not to underestimate the benefits of using a walking stick when ascending steep terrain, unfortunately I didn’t pack one with me this time and I paid for it with a stretched groin muscle.

King Hassan II Mosque – Casablanca

The next day I took the train to Meknes, but my plan was to buy the ticket for Meknes in Casablanca. Everyone who I’ve talked to, or read about visiting Casablanca, has hated it. But one thing they all share in common is they say the King Hassan Mosque is worth visiting. So I decided to just do that. I got off the station at Casablanca and left my luggage at the Super Tours office which is on the left side of the station as you walk out, they will take a small fee, and if it’s closed, as it was when I got there, knock on the window and the security guard should open it. From here, don’t do what I did and take a taxi from the station, which again I knew shouldn’t have done anyway. The guy who talked to me first told me he would take 100 dirhams, then his manager told me it would be 60. If you walk less than two minutes away from the station you can hail a petit taxi and they will charge something around the 10 dirham mark using the meter. Of course given the fact that the Moroccan Dirham is quite weak compared to the pound, none of these prices make a huge difference, but it’s the principle! The mosque is quite impressive, but like most grand mosques built by kings and sultans, because they’re so big they need to built where either no one, or very few people live. So the only people who are actually praying in the mosque are visitors and tourists, the actual spiritual benefit it provides the people of the locality versus the ego of the patron is up for debate. After praying Asr at the mosque I made my way back to the station, had a quick lunch, and caught my train to Meknes.

One thing people need to be aware of if they’re on a train that’s heading in the direction to Fez, is you’ll almost always end up with someone meeting you on the train, acting very casually, and eventually after a little while they’ll offer to put you up in their relative’s riyad, or book you a tour with one of their best mates. My general advice would be don’t bother. I’ll get to Fez in a little while, but on this particular trip I had someone a few years younger than me, with no luggage, who told me he had come from Germany to visit his family in Fez. (On my last trip it was someone who sold Moroccan goods from Fez in America). Once he found out I was going to Meknes, and I already knew my way around Fez anyway, he proceeded to tell me about the family problems he was having back in Germany. A part of me thinks he was genuine in that regard and I offered him some words of advice, but I still think he was a fixer.

Somewhere in Meknes…

A lot of people who visit Meknes, including tour guide writers, will tell you how people in Meknes are much more honest, relaxed and hassle-free compared to Fez. On exiting the station and asking how much a taxi to Bab al-Mansour would cost I was told 20 dirhams, around £1.50, ‘Wow these people really are honest’, I thought to myself. As the driver slowed down to make a turn he asked me a question, which I didn’t understand, as he made the turn and stopped, he pointed to a run down hotel with a sign on the front that said ‘Bab al-Mansour’, I realised he was asking me whether I wanted Bab al-Mansour square or the hotel, on telling him it was the former he informed me the price was actually 50 dirhams. So much for Meknesian hospitality.

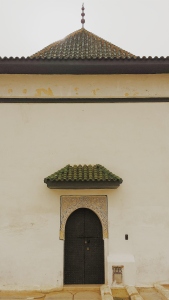

Meknes certainly is the most modest of the imperial cities of Morocco, you can see the souq, the mausoleum of Moulay Ismail and the Musée Dar Eljamîi within a few hours. I even walked to the ruins of Moulay Idris’s stables all the way around the king’s palace and back and still had plenty of time to burn. But the main thing I wanted to visit in Meknes was the zawiyah of Shaykh Muhammad ibn al-Habib. Shaykh Muhammad, is probably most famous for being the Shaykh of Abdul Qadir al-Sufi, whose Murabitun movement at one point, and even to a certain extent today, contained numerous translators, artists and scholars from the UK and elsewhere, including Shaykh Hamza Yusuf and Shaykh Abdal Hakim Murad. I spent a good part of my first morning in Meknes looking for the zawiyah, initially thinking it was located next to the Zeitouna mosque, which in turns out it wasn’t (The mosque was undergoing extensive refurbishment anyway). In the evening I managed to get in contact with brother Waseem from Sa’dah who helped me out. The zawiyah is located on Boulevard El Habboul, look for this door which leads to an alleyway (photos provided courtesy of Brother Waseem). Edit (2nd September 2017): Aaminah Patel visited the zawiyah recently and the outside has been refurbished, she kindly sent me her photos, so I’ve edited the post to include updated images:

This door leads to an alleyway.

Which in turn leads to this door with a sign above it…

“The Shadhiliyya-Habibiyya zawiyah is only open for specific prayer and visitation only”. (I don’t know what the last line means).

If the door leading to the alleyway is locked the caretaker Sidi Ali, (who is mentioned in Michael’s book), is usually standing outside and he will open it for you (Edit 2nd September 2017: Unfortunately Sidi Ali has now passed away, I don’t know who the new caretaker is, nor if they will be at the zawiyah for most of the day. You’re best to arrive at prayer time). I arrived between Maghrib and Isha and found three of the fuqara, including Sidi Ali, having a meal with bread and olive oil. They were very welcoming and it was refreshing to be able to have a conversation in classical Arabic for a while, and to be able to talk to normal Moroccans who weren’t touts or faux guides. If you don’t speak French or Arabic you may want to consider taking someone along with you, but even if you don’t, they’ll still be very welcoming. After praying Isha I had the great privilege of meeting one of Shaykh Muhammad’s wives. I was quite surprised there was anyone left from his immediate family given the Shaykh was 100 when he passed away nearly forty years ago. After Isha, a meal of lentils and bread was served, followed by one of the young fuqara, who I believe was from the family of the Shaykh, singing odes from the Shaykh’s diwan. At the conclusion I took their permission and left for the evening so they could carry on with their conversations. (I think they had enough of talking fusha for one evening).

The next day I took a grand taxi to visit Moulay Idris Zerhoun and Volubilis. You can take a grand taxi near the French Institute in the Ville Nouvelle, they’re usually meant to be shared, but I had no one to share with so I had to pay for the whole thing. You can negotiate a price depending on how long you want the driver to wait for you and what you want to see. Moulay Idris Zerhoun is a town in the mountainside built around the tomb of Moulay Idris I, founder of the Idrisid dynasty, and establisher of the first Islamic state in what is now Morocco. From his lineage comes many of the modern day descendants of Ahlul Bayt from North Africa such as Shaykh Muhammad al-Yaqoubi and Shaykh Ahmad Saad. Sidi Khalid Williams describes Moulay Idris I as the patron saint of the Moroccan state, which is a pretty accurate description, his tomb is an important place of visitation in Morocco, including by the king and the royal family. Much like Pakistan, some people have taken up strange customs when visiting shrines of saints, such as placing candles on or near tombs, or pouring rose water over them. In some places some of the caretakers will stop people from doing such things, but they’re not always heeded. When I visited there were a group of Mirpuris from North England placing their face on the cenotaph in imitation of some of the Moroccans, funny how much our two cultures have so many things (good and bad) in common from one end of the world to the other. The one thing I really disagreed with however were a group of singers who take money and will offer supplication for the benefactor. As if making d’ua has some sort of price. Saying that I will admit their performance of Qasida Burda in the Andalucian style made famous by Shaykh Hamza and the Fez Singers was wonderful to listen to, and in return I gave them some coins (though I think they were a bit confused when I walked away when they started to make d’ua). From there my driver took me to Volubilis, the ruins of a Roman city which probably served as the focal point for Moulay Idris to build his capital nearby. To know what anything is you will need a guide, but I wasn’t too fussed myself personally. With that my time in Meknes had come to an end, while Meknes is worth visiting I wouldn’t recommend bothering to stay there. You could easily arrange a day trip from Fez to Meknes, Moulay Idris and Volubilis.

Qarawiyyin Mosque – Fez

The next day I took the train to Fez, a quick 20 minute journey, to save some money you could take a bus, but I wanted to get there in time for Friday prayer at the Qarawiyyin mosque. Arriving at Fez station I really wasn’t in the mood to get hustled by another taxi driver (The one on the way out from Meknes had also tried it but luckily I got away with my precious £1.50 saved). After unsuccessfully attempting to hail a taxi from the surrounding roads I used Google’s trusty offline maps to get me from the station to the riad in the medina, it was around an hour’s walk so I wouldn’t recommend it if you don’t have the legs, and aren’t as crazy or stingy as me. Leaving my bags at the riad, I found my way to one of the main streets in the old medina and charged my way down over the old rickety slabs I remembered from my last trip. The athan had been called by the time I had arrived at the riad and most of the shops had their shutters closed. Eventually I reached a blockade of French voyeuristic tourists gathering to take pictures through a doorway, an information board next to the door told me I had arrived and as I entered the Imam had just began his khutbah, I made it just in time. On leaving one of the doormen with a wide wry smile gave salaam and offered his stool to sit on as I struggled to put on my boots, I asked him for directions to the zawiyah of Sidi Ahmed Tijani, and after doing so he asked for charity ‘for the mosque’. This was the first of two times at the Qarawiyyin that a doorman would act this way, be advised the money you give is solely for their own pocket, so if you do give them something feel free to make it as minute as possible. After visiting Shaykh Tijani I bumped into a group of brothers from High Wycombe who are students of Ustadh Haroon Hanif, I ended up inadvertently becoming their tour guide for the afternoon, and we visited Moulay Idris II and Medresa Bou (Abu) Inania, as well as having lunch at the famous Clock Cafe. After leaving them to relax back at their flat I made my way back to the Qarawiyyin to pray Maghrib and to take part in the recitation of Qur’an afterwards (to see a brief snippet I posted a video to Instagram). If you’re able to visit it’s definitely worth making the effort to attend. The next day I made my way north east of the medina towards Bab al-Fattouh. If you come this way eventually you’ll come to parts of the old city where hardly any tourists tread. When you reach the walls you’ll see in front of you the vast cemetery of Bab al-Fattouh, here there are a vast number of saints that graced the city of Fez over the centuries. The main one I wanted to visit was the tomb of Sidi Abdal Aziz al-Dabbagh. A friend had given me the number of a contact in the Muhammadiyya tariqa living in Fez to show me the tomb, but he hadn’t responded to my messages, I eventually found a hand drawn map of the cemetery online marking the tomb, and having ascertained the general area I thought I would try my luck. I didn’t need it in the end, having just entered the cemetery one of the caretakers asked me if I was looking for Abdal Aziz Dabbagh and took me where I needed to go:

Tomb of Abdal Aziz al-Dabbagh

Of course if you’re offered this service you will need to pay for it, I gave the caretaker 20 dirhams which he seemed pleased with. If you do visit Shaykh Dabbagh, it’s worth noting his tomb is visited quite frequently, and there will be others who look to gain something out of your visit. Before I had even realised a group of around six people had gathered behind me and began to recite Qur’an. I offered them some coins for their effort. The caretaker who showed me the way said something to me in Darraja and made a gesture which made me think these men also offered prayers in exchange for money. I wasn’t interested. The building over the grave is not the largest in the cemetery, but I’ve pinpointed what I believe was the location here. As you can see there’s no sign on the front except for the grave in front of the building, but there may be one on the side. The zawiyah is usually locked, but if you find the caretaker, (a picture of whom can be seen here) he will open it for you. Making my way back to the centre of the medina I thought I’d do some shopping before I left. The day before I was invited to a shop selling prayer beads very closeby to the zawiyah of Shaykh Tijani, and I found the quality of the ones the owner had were far better than others I had seen elsewhere in the city, but unfortunately he wasn’t open that day. I also managed to stumble upon the zawiyah of Shaykh al-Darqawi, the reviver of the Shadhili path in Morocco, from whom Shaykh Muhammad ibn al-Habib and Shaykh Abdul Rahman al-Shaghouri traced their spiritual lineage through. Unfortunately it wasn’t open, and besides the grave of the saint doesn’t lie here, he is buried I believe a two hour car journey away from Fez.

Fez is a great city, once you get past the touts and faux guides that put a real downer on their own country (offline Google Maps to the rescue), it’s a bustling ancient city that’s a pleasure to get lost in. For Muslims particularly it has a deep and rich spiritual tradition which offers a number of enclaves hidden away inside the storm that is the medina to offer spiritual nourishment. It was a great pleasure to visit again.

The next day I made my way to the CTM bus station to catch the 11am bus to Chefchaouen, but on arrival I was told all the buses for the day were sold out. ‘Praise to God in every state’, I thought to myself. As I flicked through my travel guide to figure out the best alternative route I could take, two women walked in with their bags towards the ticket counter, I watched them to see if an opportunity was about to arise, ‘Two tickets for Chefchaouen please’. Bingo. I asked them if they would be willing to share a grand taxi, which they were more than happy to do. So we made our way back to the old city and the other bus station to catch one.

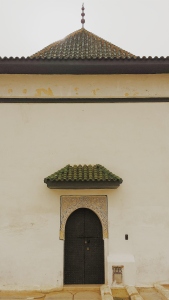

Door in Chefchaouen

Three hours later we arrived in Chefchaouen, a picturesque blue-washed city in the Rif Mountains. Googling images of the place will tell you why this place is so loved by many. The medina is quite small though, you’ll get around fairly quickly, there’s a national park and other scenic places to visit in the surrounding areas. My plan was to spend my first day seeing the city, and the next to visit Moulay Abdessalam ibn Mashish, the teacher of Imam Abul Hasan al-Shadhili. On asking the price at the grand taxi stand I was told 600 dirhams, almost as much as the taxi from Fez had cost for half the journey. The sole English speaking driver wasn’t willing to haggle, and I had no one to share the cab with. I was hoping I might bump into some Muslim tourists like I had did on the Friday in Fez but it didn’t happen. I thought I would try my luck in Tetouan the next day, but the receptionist at the riyad told me I would be looking to pay around the same there again. She recommended taking the bus that goes early in the morning from Tetouan’s main bus station, but my flight was the day after and I would be getting to Tetouan long after the bus had come back from Moulay Abdessalam. I resigned myself to my fate and decided it wasn’t meant to be. So I spent the rest of the day wandering around Chefchaouen again and making my way outside the north of the city to take pictures. One thing to be aware of is this is the heartland of Morocco’s hashish industry. You’ll get offered the stuff as you walk around, and a number of students from Spain travel down to make use of the ample opportunities to acquire it cheap.

The next day I took the CTM bus to Tetouan (this time buying my ticket a day in advance). Despite the fact Tetouan gets loads of rave reviews, I saw maybe one other tourist while I was there, a sight that is common for most people who visit it. Most of modern Tetouan was built by the Spanish, and the look and feel of the city definitely makes it apparent. My purpose in Tetouan was to visit Imam al-Harraq and Sidi Ahmed ibn Ajiba. The former is easy to find, make your way to Bab al-Maqabir in the north of the medina and you should find his zawiyah. Ibn Ajiba on the other hand is a different story, his tomb is located in the town of Mellousa, but I didn’t know its exact location. There is a large zawiyah in the area of the town called al-Zameej, but this is not the real Ibn Ajiba but actually one of his relatives. His real tomb is located a short distance away in a much more humble setting. I was hoping by the time I got to Tetouan I would hear back from someone I had emailed regarding its location, or I would come across some information from somewhere else, but that didn’t happen. You could always take a chance and book a grand taxi to take you to the main Ibn Ajiba zawiyah and then see if there are any locals there who can direct you to the real one (insha’Allah).

And that ended my swift journey to visit the saints of Morocco. Two are still left outstanding, and like a cheesy open ending finale to a movie it may lead to another journey to go back again. All knowledge rests with God. I ask Allah He accept my journey to visit his awliya, and that he allows us to continue to benefit from their works and their presence both in this life and the next. If anyone would like some advice or tips on making a similar journey feel free to get in touch.